As the tide of failure rises ever higher and the liberated masses realise they have been sucking on a lemon, the question then becomes: How do you throw the bums out, or at least make politics competitive enough to incentivise them to change their ways?

As the tide of failure rises ever higher and the liberated masses realise they have been sucking on a lemon, the question then becomes: How do you throw the bums out, or at least make politics competitive enough to incentivise them to change their ways?

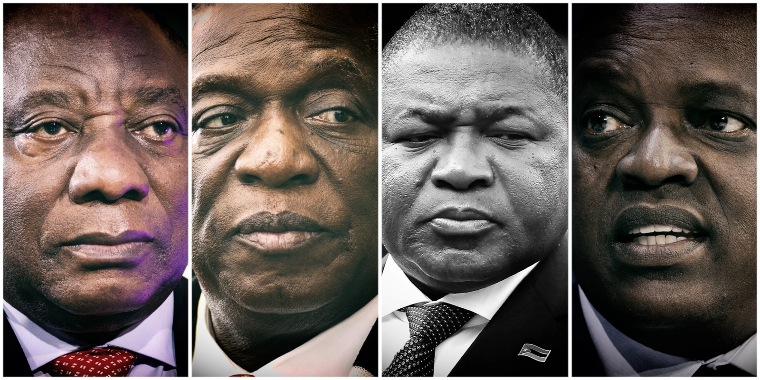

There has been much head-scratching over the failure of President Cyril Ramaphosa to go beyond rhetoric and act decisively to deal with the country’s myriad challenges, from rolling blackouts to the rapid growth of a parallel mafia state.

But Ramaphosa is not unique. He shares the inability to deal with major structural problems in governance and the economy with his fellow liberation leaders in Zimbabwe, Angola, Tanzania and beyond. The same malaise has also, curiously, gripped Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni, who liberated his country from liberators.

The answer lies in the fact that liberation movements are well suited to rhetoric and populist posturing. They can harangue you with war stories and summon demonising rhetoric, but when it comes to making decisions and acting on them with speed, they appear to sink in a molasses of indecision and rumination. Why does this pattern repeat itself?

The answer is, of course, straightforward. By the time their countries hit economic and political tailwinds, it is the liberation movements’ own leaders who are in the thick of the state’s failures, infusing the state with corruption, rent-seeking, the appointment of cronies and a culture of indifference to outcomes.

This is true across southern Africa — with the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in Angola, South West African People’s Organisation (Swapo) in Namibia, Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) in Zimbabwe, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) in Tanzania, Botswana Congress Party (BCP) in Botswana, the Liberation Front of Mozambique (Frelimo) in Mozambique and, of course, South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC).

As the tide of failure rises ever higher and the liberated masses realise they have been sucking on a lemon, the question then becomes: How do you throw the bums out, or at least make politics competitive enough to incentivise them to change their ways?

The answer is that it is not easy. In fact, it’s so difficult that — Zambia, Malawi and Lesotho aside — this has not happened since independence. Liberation movements learnt well from each other how to grasp power, and even more so how to retain it.

None of them was going to make the same mistake as Kenneth Kaunda in hosting free and fair elections, which saw the Zambian founding father and his United Independence Party (Unip) bundled out of power unceremoniously in 1992 — that is, until Edgar Lungu was similarly deposed by Hakainde Hichilema in the elections in Zambia in 2021. Kamuzu Banda’s fate in Malawi in 1994 offered another reminder not to allow an open and competitive process.

Continued next page

(397 VIEWS)