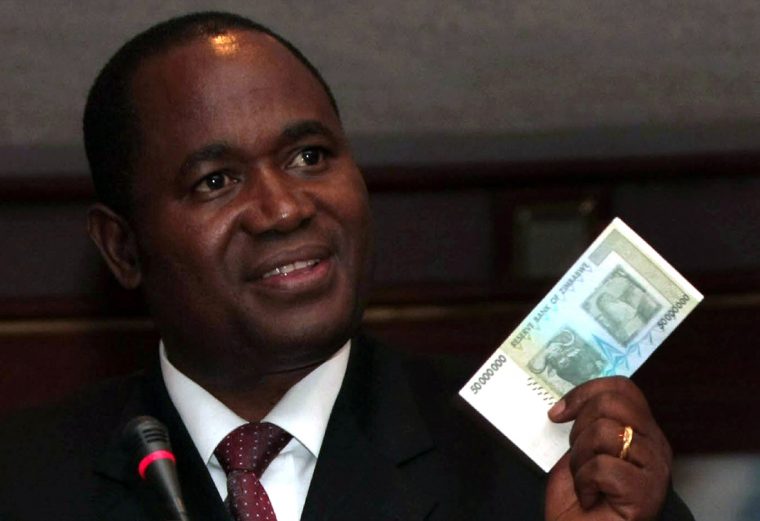

When Gideon Gono’s term ended at central bank, he left a $1.3 billion debt. But the bigger, more damaging deficit he left was public trust.

In December 2014, as the economy struggled with the big problem of small change, the bank introduced bond coins. Stores had been handing out everything from matches to teaspoons as change, if they were not ripping customers off by rounding off prices.

The immediate public reaction to the bond coins was predictable. This was an opening for the Zimbabwe dollar to sneak back in, critics said.

Few things strike fear into the heart of a Zimbabwean than the word “Zimdollar”. Social media platforms were on fire, opposition politicians told people to run for the hills and economists predicted doom.

But not long after its launch, the bond coin ran into some good fortune. The rand, the small change of choice in Zimbabwe, tanked. Commuter omnibus crews began preferring bond coins over rand coins and, suddenly, the much derided bond coin was in business.

And that is how it worked for the bond coin, market forces and the ruffian combi crews, and not the words of John Mangudya, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) governor.

When he took over at RBZ in May 2014, Mangudya found a central bank up to its eyeballs in debt. A few legal steps and some of that legacy debt was soon off his shoulders. But the one deficit he inherited from Gono, that big gap in public confidence in the bank, remains the one he is still struggling to shrug off. Confidence is the one thing no bank can afford to lose, least of all a whole central bank.

When he launched bond coins, he had made fairly plausible explanations. This was a necessary step, the coins had real value as they were backed by real money, and this system had worked elsewhere.

These were rational explanations, if they were being made to a perfectly rational audience, and by a bank that itself has acted rationally in the past. Sadly for Mangudya, the 10 years before his term are a case-study in how to kill a nation’s confidence in its own central bank.

Gono’s monetary policy had been anchored on uncertainty, which he wielded like a weapon, making him one of the most powerful people in the country.

In the end, we began to expect a new crisis to follow any economic announcement. A new currency overnight, new prices, sudden new rules that forced us to change, within hours, the way we lived our very lives. How many times did the words “with immediate effect” drive us into panic?

The result was a collapse in public trust in RBZ, or in any government institution and indeed the government itself. They could not be trusted to make economic decisions that made people’s lives better.

Continued next page

(465 VIEWS)