Bindura South is a rural constituency that saw waves of violence and displacement in 2008, and We The People is seeing a high number of reports from there this year, too. On a trip to the area in early July, nearly everyone interviewed agreed that Zimbabwe is somewhat freer under Mnangagwa than Mugabe. But the trauma of 2008 is still very much alive.

In April 2008, Clifton Mawire, then 23, had his hands tied behind his back before being shoved to the ground and beaten with wooden planks. He knew the men who thrashed him — they had grown up together. As they beat him, they asked, “Why don’t we see you at the ZANU rallies? Are you an MDC supporter?”

Mawire says this year’s election feels a bit too much like 2008 to him for comfort.

“Right now, Mnangagwa is preaching peace to the world, but here ZANU is saying, ‘We know who you are, we will know who you voted for, we have your fingerprints,’” said Mawire.

The government has instated a biometric voter registration system, which has figured regularly in reported threats and raised fears, likely unfounded, that the vote will not be secret.

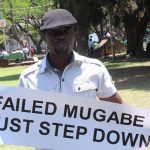

On the surface, plenty else does look different a decade after 2008. Mugabe is not only relegated from power, but many ZANU-PF supporters speak openly about his brutality and mismanagement of the economy. Mnangagwa’s campaign is centered on “opening up Zimbabwe” for foreign investment, rather than the anti-imperialist rallying cries that made Mugabe famous.

Some ZANU-PF and army officials are still subject to international sanctions but are hoping the appearance of a free and fair election will help lift them.

Outcry over reports of irregularities has been lukewarm in part because ZANU-PF’s opposition isn’t as strong as it could be. Morgan Tsvangirai died after a long battle with cancer in February, and a 40-year-old lawyer named Nelson Chamisa has taken the helm.

He speaks, improbably, of turning the country into a technology hub. He is prone to histrionics, saying he’ll boycott the election one day, and relenting the next. MDC posters are rare, compared to the ubiquitous Mnangagwa banners, but they aren’t torn down immediately, like in the past.

Over decades in power, ZANU-PF conflated itself with the state, developing pervasive systems of patronage and controlling access to information. The party also demonstrated what could happen to dissenters: denial of public services, social ostracism and in extreme cases, disappearances and killings.

The army and police are widely perceived to be on their side, though the army reaffirmed its neutrality in a statement this month.

On a recent day in the call center, however, volunteers got a call from a farmer named Saini Saini, from the Gokwe North district. He said that local ZANU-PF supporters came to his home and said they would kill him if he voted for Chamisa.

“How can I report this to the police when they themselves openly wear ZANU-PF regalia?” said Saini. “We need help.”

Continued next page

(392 VIEWS)