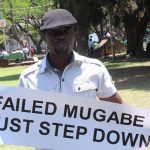

Most Zimbabweans have only ever known one president: Robert Mugabe.

Most Zimbabweans have only ever known one president: Robert Mugabe.

But on 30 July, a new man will represent Zimbabwe’s ruling party on the ballot for the first time in 38 years. Emmerson Mnangagwa, who went from being Mugabe’s right-hand man to his unseater, has taken the reigns.

Although he’s a party stalwart, Mnangagwa, 75, has cast himself as a beacon of change. And after decades of authoritarian rule that isolated Zimbabwe, he is promising to end the political violence and intimidation that characterized Mugabe-era elections.

International observers are now in Zimbabwe for the first time in decades. But accounts from opposition supporters in this rural constituency (Bindura South), 80 km from the capital city of Harare, shows how the ruling party’s intimidation and patronage apparatus is still very much intact.

While observers have so far avoided saying outright that the campaign season has not been “free and fair,” human rights organizations and opposition groups are compiling an ever-growing number of reports of electoral malpractice, including death threats to opposition candidates, forced attendance at rallies and the distribution of government handouts to Mnangagwa supporters.

(Only a small fraction — less than 50 reports so far — have indicated physical violence.)

Since mid-June, more than 500 reports have streamed in from all of Zimbabwe’s provinces, and nearly all were attributed to Mnangagwa’s party, ZANU-PF. A consortium of seven civil society organizations, operating together under the name We The People, have set up a call center to field and verify the reports.

The benchmark for most Zimbabweans is the 2008 election. That year, Mugabe lost the first round to his perennial challenger, Morgan Tsvangirai, leader of the main opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change, or MDC.

Between the election and the runoff, ZANU-PF and the military carried out a campaign known internally as CIBD: coercion, intimidation, beating and displacement. More than 80 were killed and Tsvangirai himself was brutally beaten.

“The intimidation is more subtle this time. The modus operandi has changed but the message is the same as it was under Mugabe: ‘If you choose the wrong side, the violence will be terrible,’ ” said Zachariah Godi, who works with We The People to verify the reports the call center receives.

Continued next page

(392 VIEWS)