In retrospect, it’s widely recognised that the challenges they faced were immense. Most post-colonial economies were underdeveloped and depended upon the export of a small number of agricultural or mineral commodities. From the 1970s, growth was crowded out by the International Monetary Fund demanding that mounting debts be surmounted through the pursuit of structural adjustment programmes. This hindered spending on infrastructure as well as social services and education and swelled political discontent.

In contrast, Mugabe inherited a viable, relatively broad-based economy that included substantial industrial and prosperous commercial agricultural sectors. Even though these were largely white controlled, there was far greater potential for development than in most other post-colonial African countries.

But, through massive corruption and mismanagement, his government threw that potential away. He also presided over a disastrous downward spiral of the economy, which saw both industry and commercial agriculture collapse. The economy has never recovered and remains in a state of acute and persistent crisis today.

On the political front, the rule of some leaders – like Milton Obote in Uganda and Siad Barre in Somalia – created so much conflict that coups and crises drove their countries into civil war. Zimbabwe under Mugabe was spared this fate – but perhaps only because the political opposition in Matabeleland in the 1980s was so brutalised after up to 30 000 people were killed, that they shrank from more conflict. Peace, then, was merely the absence of outright war.

Some leaders, notably Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, are still revered for their commitments to national independence and African unity. This is despite the fact that, domestically, their records were marked by failure. By 1966, when Nkrumah was displaced by a military coup, his one-party rule had become politically corrupt and repressive.

Despite this, Nyerere always retained his reputation for personal integrity and commitment to African development. Both Nkrumah’s and Nyerere’s ideas continue to inspire younger generations of political activists, while other post-independence leaders’ names are largely forgotten.

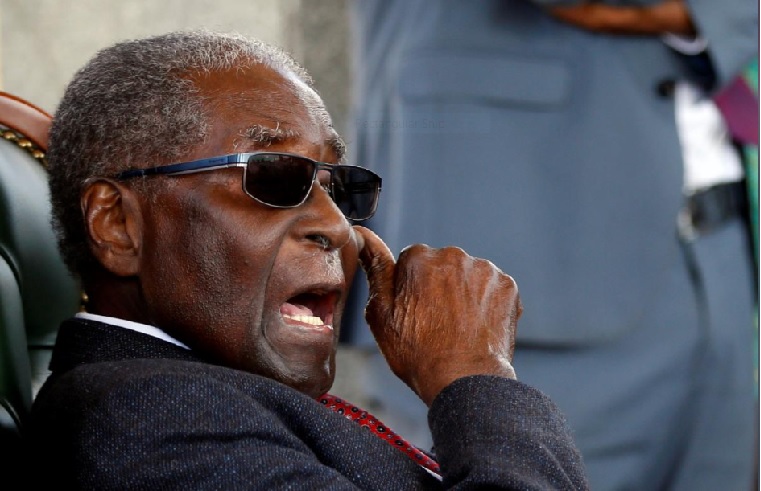

Will Mugabe be similarly feted by later generations? Will the enormous flaws of his rule be forgotten amid celebrations of his unique role in the liberation of southern Africa as a whole?

The problem for pan-Africanist historians who rush to praise Mugabe is that they will need to repudiate the contrary view of the millions of Zimbabweans who have suffered under his rule or have fled the country to escape it. He contributed no political ideas that have lasted. He inherited the benefits as well as the costs of settler rule but reduced his country to penury. He destroyed the best of its institutional inheritance, notably an efficient civil service, which could have been put to good use for all.

The cynics would say that the reputation of Patrice Lumumba, as an African revolutionary and fighter for Congolese unity has lasted because he was assassinated in 1961. In other words, he had the historical good fortune to die young, without the burden of having made major and grievous mistakes.

In contrast, there are many who would say that Mugabe simply lived too long, and his life was one of Greek tragedy: his early promise and virtue marked him out as popular hero, but he died a monster whom history will condemn.

By Roger Southall for The Conversation

(120 VIEWS)