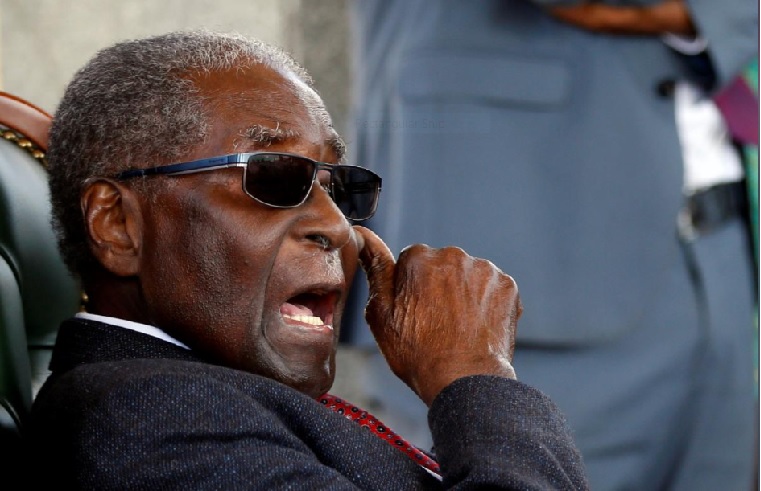

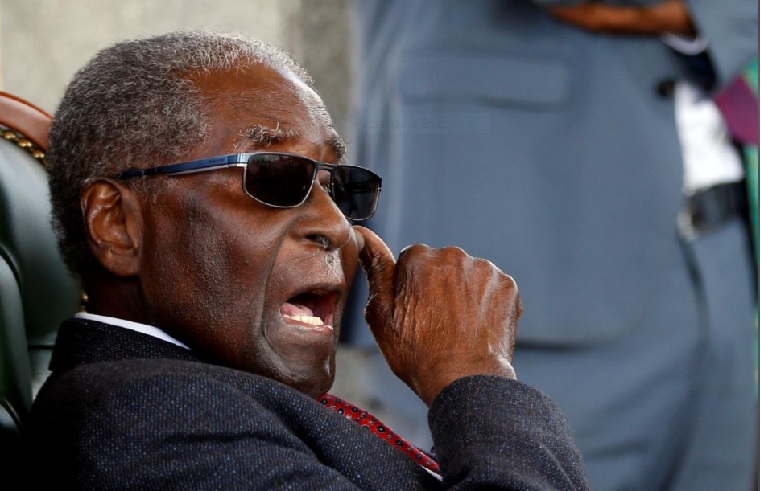

Robert Mugabe, the former president of Zimbabwe, has died. Mugabe was 95, and had been struggling with ill health for some time. The country’s current President Emmerson Mnangagwa announced Mugabe’s death on Twitter on September 6: “It is with the utmost sadness that I announce the passing on of Zimbabwe’s founding father and former President, Cde Robert Mugabe.”

Robert Mugabe, the former president of Zimbabwe, has died. Mugabe was 95, and had been struggling with ill health for some time. The country’s current President Emmerson Mnangagwa announced Mugabe’s death on Twitter on September 6: “It is with the utmost sadness that I announce the passing on of Zimbabwe’s founding father and former President, Cde Robert Mugabe.”

The responses to Mnangagwa’s announcement were immediate and widely varied. Some hailed Mugabe as a liberation hero. Others dismissed him as a “monster”. This suggests that Mugabe will be as divisive a figure in death as he was in life.

The official mantra of the Zimbabwe government and its Zimbabwe African National Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) will emphasise his leadership of the struggle to overthrow Ian Smith’s racist settler regime in what was then Rhodesia. It will also extol his subsequent championing of the seizure of white-owned farms and the return of land into African hands.

In contrast, critics will highlight how – after initially preaching racial reconciliation after the liberation war in December 1979 – Mugabe threw away the promise of the early independence years. He did this in several ways, among them a brutal clampdown on political opposition in Matabeleland in the 1980s, and ZANU-PF’s systematic rigging of elections to keep him and his cronies in power.

They’ll also mention the massive corruption over which he presided, and the economy’s disastrous downward plunge during his presidency.

Inevitably, the focus will primarily be on his domestic record. Yet many of those who will sing his praises as a hero of African nationalism will be from elsewhere on the continent. So where should we place Mugabe among the pantheon of African nationalists who led their countries to independence?

Most African countries have been independent of colonial rule for half a century or more.

The early African nationalist leaders were often regarded as gods at independence. Yet they very quickly came to be perceived as having feet of very heavy clay.

Nationalist leaders symbolised African freedom and liberation. But few were to prove genuinely tolerant of democracy and diversity. One party rule, nominally in the name of “the people”, became widespread. In some cases, it was linked to interesting experiments in one-party democracy, as seen in Tanzania under Julius Nyerere and Zambia under Kenneth Kaunda.

Even in these cases, intolerance and authoritarianism eventually encroached. Often, party rule was succeeded by military coups.

In Zimbabwe’s case, Mugabe proved unable to shift the country, as he had wished, to one-partyism. However, this did not prevent ZANU-PF becoming increasingly intolerant over the years in response to both economic crisis and rising opposition. Successive elections were shamelessly perverted.

When, despite this, ZANU-PF lost control of parliament in 2008, it responded by rigging the presidential election in a campaign of unforgivable brutality. Under Mugabe, the potential for democracy was snuffed out by a brutal despotism.

Whether the economic policies they pursued were ostensibly capitalist or socialist, the early African nationalist leaders presided over rapid economic decline, following an initial period of relative prosperity after independence.

Continued next page

(117 VIEWS)