“Zimbabwe will be an upper middle-income country by 2030” is a slogan that officials in the country love repeating. But this would need unlikely growth rates of between 8%-9% over the next seven years, according to a new World Bank report.

“Zimbabwe will be an upper middle-income country by 2030” is a slogan that officials in the country love repeating. But this would need unlikely growth rates of between 8%-9% over the next seven years, according to a new World Bank report.

Becoming an upper middle-income country (UMIC) by 2030 would require a “significant acceleration of productivity growth and focus on ensuring the creation of quality jobs”, according to the World Bank’s Zimbabwe Country Economic Memorandum (CEM), launched yesterday.

“Simulations show that Zimbabwe will need to reach productivity growth rates of 8–9% per year in the next seven years to advance to UMIC status. Achieving such unprecedented rates for Zimbabwe will require dramatic improvement in the policy environment to address the binding constraints to productivity growth,” the World Bank says.

The 8%-9% growth targets are far higher than the growth estimates for Zimbabwe.

The World Bank estimates that the economy will grow by 3.6% this year and 2024. The Bank says Zimbabwe’s economy grew by 5.8% in 2021, recovering from the 6.2% contraction in 2020. The IMF estimates that the economy grew by 7% in 2021, and that it will grow by 3.5% this year. The government’s own growth projection for 2022 is 4.6%.

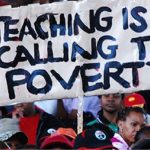

According to the World Bank, Zimbabwe’s economy is too informalised, with the largest informal sector in the world relative to its economy. This means the country cannot provide the quality of jobs that make an upper-middle-income economy. Only 33% of Zimbabwean workers receive a salary, well below peers in the region, suggesting a limited share of quality jobs despite workers possessing relatively higher skills.

“The informal sector has been the largest employer in Zimbabwe over the last four decades, suppressing productivity growth and long-term development. Presently, informal activity accounts for nearly two-thirds of Zimbabwe’s output and four-fifths of its employment, which is higher than the average level in Lower-Middle Income Countries and UMICs.”

Zimbabwe is unproductive, and its economic policies make it harder for formal firms to flourish and to attract the level of investment the country needs to graduate into an upper-middle-income economy.

“Countries that have transitioned to UMIC status have seen an improvement in the economy with extreme poverty falling, more jobs created, and easier access to health, education, and social protection,” says Marjorie Mpundu, World Bank Country Manager in Zimbabwe.

“Inefficient allocation of resources has discouraged the entry of new, potentially productive firms, forced productive firms to exit, and allowed the survival of less competitive firms. Informality and low learning from international markets also are among the key drivers behind weak productivity performance,” says the World Bank.

The Bank estimates that labour productivity in informal firms is only a fraction of the labour productivity in similar formal firms. It says competition from informal firms tends to lower the productivity of formal firms by around 24% on average, compared with firms that do not face such competition.

Zimbabwe needs to boost trade, the World Bank says. While its exports are growing, these are mostly commodities destined for a few markets.

“Zimbabwe’s economy remains highly concentrated with few firms and industries, and a small number of export products—mostly minerals and tobacco—generating the bulk of foreign exchange revenues. The agriculture sector continues to retain a sizeable share of production and employment in the economy and the bulk of lending, with significant government support and intervention. At the same time, higher value-added sectors, such as manufacturing and high-productivity services, employ a smaller share of workers and have a lower share of lending.”- NewZWire

(64 VIEWS)