On July 30, Zimbabweans will elect a new president for the first time without Robert Mugabe’s name appearing on the ballot.

On July 30, Zimbabweans will elect a new president for the first time without Robert Mugabe’s name appearing on the ballot.

Most poll watchers expect the vote, at least on a surface level, to be peaceful and orderly. Given the woefully low bar set by Zimbabwe’s political leadership — which has presided over nearly four decades of violent and brazenly manipulated polls — this could even be the least-worst election in a generation.

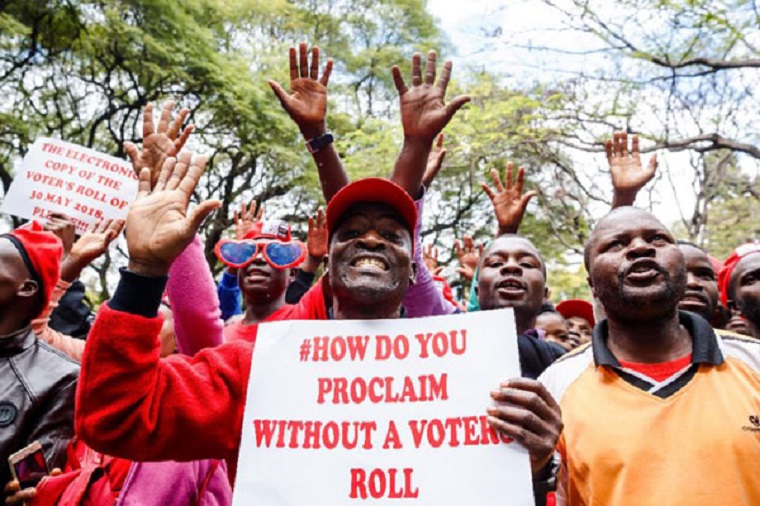

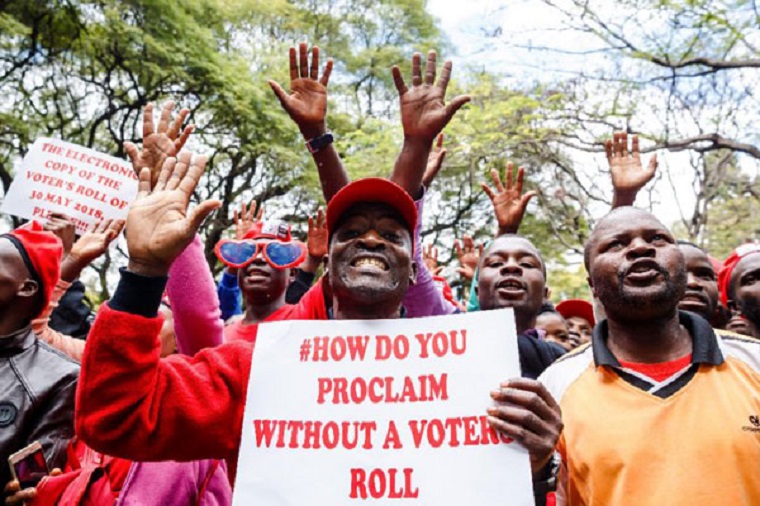

It is now less than a week until the polls open. However, the actions taken by the new government of Emmerson Mnangagwa have already made a free, fair, and credible election impossible.

Just last week, for example, the country’s electoral commission – already viewed as a partisan institution that favors the ruling party – changed the position of polling booths so that they are now in full view of officials and political party agents, a move that fatally undermines the secrecy of the ballot.

(ZEC has since agreed to revert to the old booths-Ed)

Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s longtime enforcer and bag man, is the incumbent. He rose to power last November in the aftermath of a military coup, which played out live on national television.

Mnangagwa and his cabal of generals-turned-politician desperately need international approval and political legitimacy. They are anxious to have a mountain of debt owed to the World Bank and other lenders forgiven so they can start borrowing again.

Some international observers appear ready to rubber stamp the vote despite rising concerns. The African Union (AU), for example, is hoping for elections to be minimally acceptable, with anything short of widespread violence likely to be given the stamp of approval.

One ominous signal: to lead their delegation, the AU has tapped former Ethiopian leader Hailemariam Desalegn, whose party often won elections with 100 percent of the vote.

The British embassy in the capital Harare is also thought to be especially eager to normalise relations with Zimbabwe if the poll is “good enough.” A crude ethos has seemingly developed that a lack of violence somehow equates to a credible election. It does not.

On the contrary, however, the United States, Canada, Australia, and the European Union have been more skeptical. They collectively argue that Zimbabwe’s standard should not be merely surpassing its deeply flawed past, but rather following the country’s constitution, as well as regional standards and international norms, including the AU Charter on Democracy Elections and Governance.

Continued next page

(986 VIEWS)