The Zimbabwean election campaign is in full swing. But despite the efforts of the government to improve its reputation, the politics of fear continues to undermine the prospects for a free and fair election.

The Zimbabwean election campaign is in full swing. But despite the efforts of the government to improve its reputation, the politics of fear continues to undermine the prospects for a free and fair election.

You wouldn’t know this sitting in Harare, the capital, where it has become impossible to move around without seeing a giant billboard with a picture of the country’s new leader, Emmerson Mnangagwa.

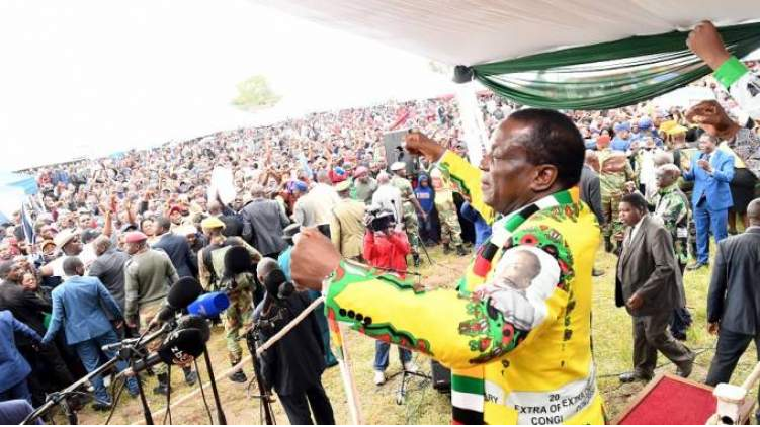

Having replaced Robert Mugabe after he was forced from power by the military in November, Mnangagwa is desperate to present himself as a “change” candidate. As a result, he finds himself in the strange position of running against the legacy of his own party.

But many Zimbabweans don’t believe the hype. “I don’t know,” one opposition supporter told me. “People are saying that this time it will be different, but a leopard doesn’t change its spots — so what can we expect from a crocodile?”

The mention of a “crocodile” is a reference both to Mnangagwa’s nickname and to the concern of many Zimbabweans that someone who was previously one of the most brutal members of the Mugabe government cannot be trusted to respect human rights.

There are some positive signs. Having promised elections observed by international monitors — something that was not allowed under Mugabe — the President has delivered.

The presidential and legislative polls on 30 July will be watched by observers from the European Union and the United States.

Police have a less visible presence on the streets. The High Court recently ordered chiefs to stop campaigning for the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), and the opposition has been able to hold rallies in rural areas.

Yet despite this, a shocking number of Zimbabweans still feel afraid. According to a nationally representative survey conducted by the Afrobarometer in May, 31 percent worry that their ballot is not secret, 41 percent believe that the security forces will not be willing to accept the results, and 40 percent fear that there will be violence after the polls.

These figures suggest that many voters believe the regime will be able to tell who voted for the opposition, and to punish them. Things may have changed somewhat after the recent pledge of the Zimbabwe Defense Forces (ZDF) not to intervene in the process, but these fears run deep. A free and fair election simply cannot be held in such a context.

While it is historically rooted, the prevalence of fear among the electorate is no accident. For all of the progress under Mnangagwa, ZANU-PF’s remarkably effective system of political control continues to operate.

Continued next page

(287 VIEWS)