Zimbabwe’s governing ZANU-PF is earnestly courting international legitimacy as the country approaches its first post-independence elections without Robert Mugabe.

Zimbabwe’s governing ZANU-PF is earnestly courting international legitimacy as the country approaches its first post-independence elections without Robert Mugabe.

The party frequently uses clichés like “fresh start”, “new dispensation”, and “open for business” to signal its willingness to engage with the West. The talk has been matched by some action.

The government has repudiated most of its indigenisation legislation, and recently applied to re-join the Commonwealth. Additionally, 46 countries and 15 regional bodies have been invited to observe the elections. This includes many Western nations that had been excluded in recent years.

Their assessments will probably not be decided by technical factors. It seems unlikely that ongoing debates over the voter’s roll or the prominence of ex-military personnel in the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission will have much impact on the final judgements passed by the monitoring missions.

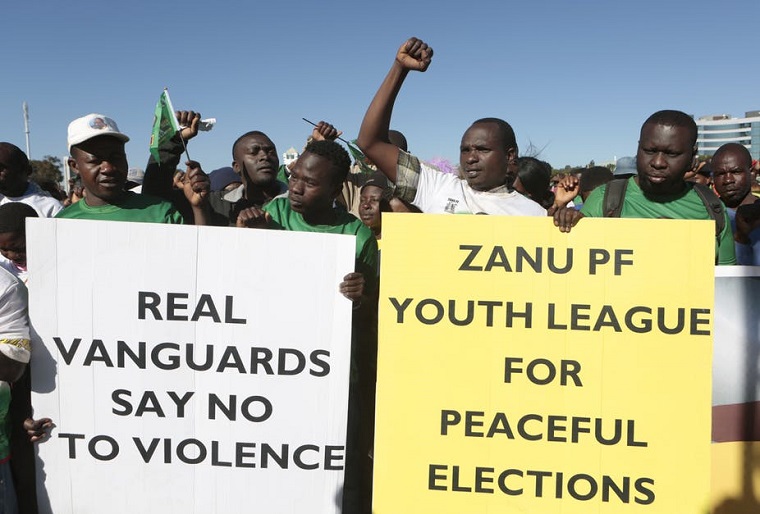

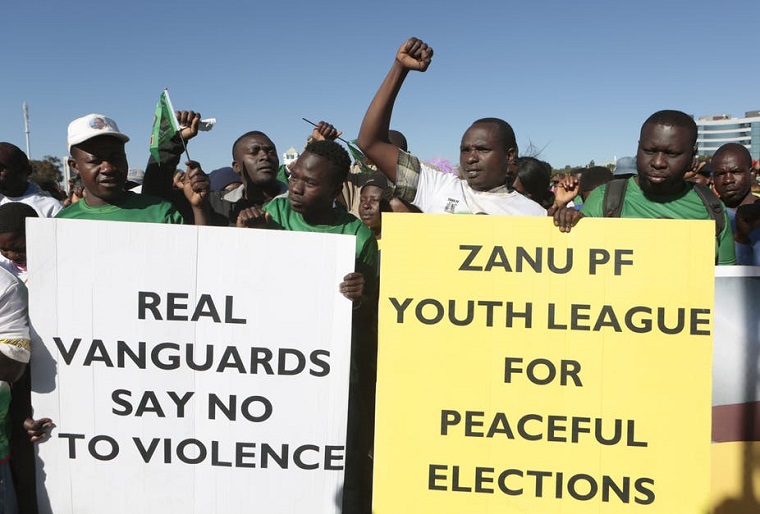

It’s more likely that the credibility of the elections will be shaped by issues such as political violence and media freedom. In both spheres, the legacy of colonialism and the liberation struggle weigh heavily.

As a breakaway party from the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) in 1963, the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) emerged in a very fragile position. It endured violence against its members and was denied access to a free media. In later years, the party perpetrated and perpetuated the same tactics under which it was conceived – both as a liberation movement and in government.

There are a number of examples of how ZANU-PF drew on colonial-era repressive tactics in its post-independence quest for political primacy. These include the Gukurahundi violence under the Mugabe led government in the 1980s against areas predominantly supporting ZAPU, the government’s 2005 Operation Murambatsvina which targeted properties belonging mostly to urban opposition supporters, and the 2008 election run-off violence after Mugabe lost the first round of voting.

As Zimbabweans head to the polls on 30 July, this history looms large over the electorate and those responsible for overseeing its successful execution.

In July 1960, unprecedented protests in Zimbabwe’s two largest cities ushered in a new era of political violence in the British colony. A year later violence erupted within the liberation movement itself.

In June 1961, the first significant attempt to form a breakaway nationalist movement in Zimbabwe was thwarted. Members of the Zimbabwe National Party (ZNP) were physically prevented from launching the party at their own press conference by National Democratic Party (NDP) sympathisers.

The ill-fated efforts of the ZNP would have been prominent in the minds of ZANU founders when it was formed two years later.

Continued next page

(194 VIEWS)